Let's talk about Hodler. Ferdinand Hodler is a Swiss painter, born in 1853, died in 1918. He is very well known by amateurs of turn of the century, symbolist art. I came across Hodler's work a long time ago. I remember being completely mesmerised by his "Eiger, Mönch and Jungfrau über dem Nebelmeer", displayed at a show in the London Hayward Gallery in 1994. Recently I picked up a beautiful catalogue of his landscapes (published by Scalo, 2004) in a bargain bookshop. And so my fascination for this painter got a new impulse.

The reason why I am interested in Hodler is because he has explored the subject matter of mountains as no other painter before or after him has done (apart, perhaps, from his contemporary Giovanni Segantini). He painted about 250 landscapes, the majority of which featured mountains in some way. The earliest in the book dates from 1871. His style had fully matured by 1905. I am very interested in what Hodler does with these mountains, the way he approaches them compositionally, the syntax of this landscape work. Much of what I see reminds me of what I'm trying to do in my own series of photographic mountain portraits. But that resemblance may be deceptive.

Let's first look at Hodler's compositional principles and then investigate how they related to the photographic practice of his times. Then let's try to find out what this means for my own project.

Four essays in the "Landscapes" book help us in deciphering crucial elements of Hodler's syntax. In fact, it is not so difficult to construct a typology of archetypal Hodler landscape compositions. He liked simple compositions based on obvious symmetries and geometric templates (pyramidal, striped, apsidial and ovaloid). In some cases, more complex forms were generated as superimpositions of these basic schemes.

The straightforward compositional approach is backed up on his choice of vantage points which allowed him to focus on individual mountain peaks. And so it is no surprise to see the notion of "mountain portrait" evoked by one of the authors: "(Hodler) created images that no longer showed individual mountain peaks as part of a panorama but in close up view and in almost total reduction, transforming them into individual portraits." Furhtermore, Hodler accentuated his motifs by eliminating irrelevant details, emphasising their linear structure and creating an interesting tension between reduction and tectonic complexity in the process. Hodler seemed to have said that "the viewer must be able to perceive the entire image at a glance": a thesis which deviates conspicuously from the principles held by Segantini who invited the viewer's gaze to drift across his panoramic tableaux. (Incidentally, this reminds me of the famous conversation between Mahler and Sibelius in Helsinki, 1907, where the former expounded that a symphony had to embrace the world, contradicted by his Finnish peer who thought that compositional restraint and severity of form was the clue to true symphonism).

Several authors have linked Hodler's approach to the practice of alpine photography in those early days. Sharon Hirsh, a scholar, has pointed out that both the pioneers of mountain photography and Hodler chose very similar angles and sections. Another scholar, Danielle Nathanson, has photographed numerous motifs in the Bernese Oberland from the painter's likely vantage point: "She concludes that Holder not only adhered to the natural model, but that he also framed it the way it presents itself to the human field of vision - and to a camera lens with a regular focal length (approx. 50mm)."

The deeper logic between this correspondence is hardly explained. Apparently, the simple fact that both painters and photographers made use of the technological innovations of the day and chose their vantage points near the cable car stations suffices. That argumentation is weak and I personally think it is wrong to see Hodler's work as a painterly extension of the photographic logic en vogue those days. In fact, I think they may in some ways be very much at odds.

For a start, one should not forget that by the time Hodler developed his mature style, end of the 19th century, photography was around already for a long time. Gregory Batchen has commented on the fact that photography was a technological innovation that, long before the days of globalisation, diffused astonishingly rapidly across the globe. By 1900, photography had been well entrenched for around 50 years. Just as television is a taken for granted fixture in our current media environment, so photography must have long lost its avant-garde lustre already by the time Holder got to work earnestly. Indeed, early examples of Alpine photography date already from the 1850s, not from the 1880s as Hirsh seems to suggest. In the late 19th century, Alpine photography had even been thoroughly commercialised: studio portraits were made in heroic poses against the background of a mountain decor and "Kaufbilder" (postal cards) with mountain scenes were all over the place.

Rather than to extend the photographic logic, Hodler may have been interested in "saving" the mountains from disappearing in this inflation of technically reproduced images. So, he paints iconic portraits of mountains, reducing them to their very essence (an essence which photography, infatuated by its ability to reveal tectonic complexity, often obscured) and investing them with a metaphorical rhetoric (cloud arabesques, mystic light) that is at odds with the documentary ethos of contemporaneous photography. Seen from this angle, Hodler's project consisted essentially in salvaging the notion of "the sublime" that had been drifting around the (visual) experience of the mountain world since Edmund Burke wrote his celebrated essay.

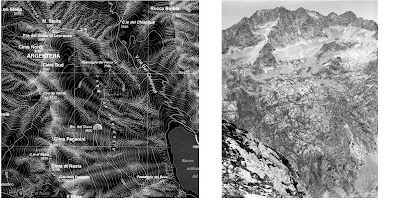

This brings me to my own photographic project. I have given the question what I really want to do with this already a lot of thought. But I don't seem to be able to come to a conclusion. I know what I want to do, but I can't explain it. Compositionally, there is a lot that reminds me of Hodler's approach: focus on isolated mountain shapes; simple iconic compositions often based on axial symmetry; compression of foreground and background; absence of any indicator of scale. What is different is indeed my interest in tectonic complexity. I use large format because I need the resolution to show the mountains' overwhelmingly chaotic, mineral textures.

Just as Hodler may have been, I too am interested in salvaging the mountain from being reduced to a mere simulacrum. Never before so many images of mountains have circulated as today. But mostly it concerns colourful, glossy eye-candy: a convenient and completely harmless backdrop to project our desires upon. Leafing through 30 years of a German mountain magazine, I noticed that, as the time went by, the photography deteriorated, the images became more indifferent and empty up to the point to where they became completely meaningless. A slightly nauseating experience.

In contemporary art photography the reverse applies: mountains are almost a taboo. Associated with smug romanticism, avoided as vestiges of a destructive logophallocentrism, they don't feature in the current photographic vocabulary. And if they do appear, then it is precisely veiled (as in Axel Hütte's matter of fact, misty landscapes or in Michael Schnabel's nocturnal fantasies), edited out (as in Walter Niedermayr's hypergraphical renderings of the circus on ski slopes) or mixed up with the phoney and the fake (as in Sonja Braas' quasi-realist studio renderings of primeval nature).

Around 25 years ago the New Topographics movement had something to say about mountains. Arguing against an edenic representation of nature, they brought in logging projects, quarries, road infrastructure, cable cars, human habitation into their landscapes. Frank Gohlke's study of Mount St. Helens is a case in point. Maybe even Burtinsky is a late shoot from this branch. But that story has been told. So the question is what story there is to tell, today, about these surprising geomorphological phenomena we call mountains?

So I keep trying to understand what it is that leads me to carry a 25 kilo backpack over dizzying via ferrata in the Dolomites. Is it a relapse into the cliché of the sublime? What is it that is so attractive and so different in these images of alpine photography pioneers? How is Hodler's programme different from theirs? Questions I don't really know the answers to. I have to continue to explore.

Above I have juxtaposed three images: on top a picture I took of the Niesen and Lake Thun in Switzerland (2005), in the middle a sketch by Hodler (probably around 1910) and below one of his finished paintings of the Niesen (1910).

I haven't almost taken any pictures lately for lack of time. But just a few days ago I demonstrated to myself once more that such a thing as lack of time is not really a good excuse. It was already past midnight and I was ready to go to bed. We'd had a visitor, Aldo, with whom I had been discussing about his poetry and the eventual possibility to combine poems with images. We'd reviewed books by Jodice, Koudelka and Arthur Tress. We'd looked at how Hans Bol had worked with poems in his book. So after Aldo had left, I was still excited about what we discussed. So when I looked outside and saw a thick, smoggy mist, it took only a minute of inconclusiveness to pick up the Fuji 645, load it with a roll of Ilford 3200 and go out for a short walk in the neighbourhood. It took me less than half an hour to shoot up the roll of 16 images. Today I picked up the film at the lab and was pleasantly surprised by the results. Lots of out of focus (exposure times of 2 secs and longer) but plenty of atmosphere. I like this little series. Plain proof that "lack of time" does not exist. Laziness however, does.

I haven't almost taken any pictures lately for lack of time. But just a few days ago I demonstrated to myself once more that such a thing as lack of time is not really a good excuse. It was already past midnight and I was ready to go to bed. We'd had a visitor, Aldo, with whom I had been discussing about his poetry and the eventual possibility to combine poems with images. We'd reviewed books by Jodice, Koudelka and Arthur Tress. We'd looked at how Hans Bol had worked with poems in his book. So after Aldo had left, I was still excited about what we discussed. So when I looked outside and saw a thick, smoggy mist, it took only a minute of inconclusiveness to pick up the Fuji 645, load it with a roll of Ilford 3200 and go out for a short walk in the neighbourhood. It took me less than half an hour to shoot up the roll of 16 images. Today I picked up the film at the lab and was pleasantly surprised by the results. Lots of out of focus (exposure times of 2 secs and longer) but plenty of atmosphere. I like this little series. Plain proof that "lack of time" does not exist. Laziness however, does.