I found “Souvenirs from High Places” (Joe Bensen, 1998, The Mountaineers), which is out of print, via a superbly interesting website:

abebooks.com. This is an umbrella-site for hundreds of second-hand bookshops all over the world. Predictably it is a veritable treasure trove for the amateur of rare or out-of-print volumes. Of course, also the lover of photographica will find more than his wallet can buy. On a first visit I limited myself to a rare copy of Koudelka’s “Wales-Reconnaissance”, a signed copy of Klett’s “Revealing Territories”, a 1941 folio with mountain photographs from the Himalayas by Vittoria Sella and a monograph on our King Albert I’s climbing activities (“Le Roi Albert Alpiniste”, 1956, by Robert Mallieux). Another book in the shopping basket was this volume on mountaineering photography.

I usually date my infatuation with photography roughly four years back, when I started to take my SLR camera back with me on trips to Ireland and Mongolia. But it is true that long before that I had been taking photographs. However, this was just a corollary to my climbing and trekking activities in the Alps, the Arctic (Iceland, Greenland) and Karakoram. Together with some of climbing partners, I cobbled together primitive slideshows only of interest to the amateur of wilderness activities. With dwindling opportunities to spend time in the mountains (marriage, children, work, etc.) also my interest in photography flagged.

Today I am getting interested again in the discipline of mountain and mountaineering photography. I have a particular kind of photography in mind which leans very much towards the severe, monumental style of the pioneers in the genre such as Vittorio Sella and the early Tairraz brothers. But with a twist of course.

Very few photographers today are taking large format black and white pictures in the mountains today. Essentially that is also the story that is told by “Souvenirs in High Places”. The whole argument of this book can be neatly summarised in a couple of key points: from the mid-18th century onwards, the popularisation of mountain sports was paralleled by a rapid diffusion of the new medium of photography. And as photographers were able to switch from cumbersome plate cameras to portable film-based devices, the attention shifted from the landscape genre to action/sports photography. All this is hardly a revelation. But the author illustrates this points profusely with a wealth of pictures from a variety of sources, which is what makes this volume worth the modest price I paid for it (there are some really interesting bits, such as another version of Bradford Washburn’s “Climbers on the Doldenhorn” than the one we are used to).

Today we see very few black-and-white pictures being taken in the mountains. But there may be faint signs of a little renaissance. Jürgen Winkler’s classic “Aus den Bergen” (originally published in 1993 and awarded with the Prix Mondial du Livre de Montagne) has been reissiued by Bruckmann Verlag (2004). And only a few months ago there was “Celestial Realm”, an imposing monograph dedicated to China’s Yellow Mountains by Wang Wusheng (Abbeville Press, 2005).

There is also very little large format being used in the Greater Ranges. The last practitioners of this arcane art, as far as I know, where men such as Bradford Washburn, Koichiro Ohmori (both, however, focusing on aerial photography) and Shiro Shirahata. A recent book such as “Sulle Vette delle Alpi” by Marco Bianchi (Mondadori, 2004) revives this ancient tradition. However, his colour photographs, although suggestively beautiful and of great documentary interest to the mountaineer, do not probe the deeper mysteries behind the baffling geological phenomena we call mountains.

So, perhaps, back to Vittorio Sella. Anyone interested in his work should read Ansel Adam’s very brief but illuminating introductory essay included in the Aperture monograph that was published a few years ago (see here for my

review of this book). It is worth quoting: “Knowing the physical pressures of time and energy attendant on ambitious mountain expeditions, we are amazed by the mood of calmness and perfection pervading all of Sella’s photographs. The exquisitely right moment of exposure, the awareness of the orientation of camera and sun best to reveal the intricacies of the forms of ice and stone, the unmannered viewpoint – these qualities reveal the reverent and intelligent artist. In Sella’s photographs there is no faked grandeur; rather there is understatement, caution, and truthful purpose. The considered compactness of Sella’s compositions is typical of good photography; there is no loose sentimentality or emphasis on obvious pictorial patterns. His compositions may appear severe to many, but his severity is actually the effect of accuracy and truth of mood.”

“Understatement”, “truthful purpose”, “severity”, “accuracy”, “truth of mood”: these are all qualities I find hugely appealing in a mountain photograph. And it is rare to find them all assembled in the same photographer. So, I imagine that I might try to get into Sella’s footsteps (of course, at a much more modest level of artistry and accomplishment): take the 4x5’ or the 8x10’ or exploratory rambles through the Alps. Focus, perhaps, on the dull days where the light bathes everything in a monochrome grey. Try to isolate simple, archetypal forms and frame them in straightforward and strong compositions. Capture the texture of sky, snow, ice, water and rock but don’t get mesmerised by any of these in particular. That is what I would like to do.

Aren’t there any contemporary examples? Yes, there are, and one of them approaches pretty much the ideal I have in mind. My attention was drawn to the work of Swedish photographer

Gerry Johansson by an article in Black & White Photography, featuring his large format work (8x10’) produced during a Swedish Antarctic expedition: stark, uncompromising images that capture the majesty of that mineral world exceedingly well. Remarkably enough, this seems to be Johansson only foray in the genre of mountain photography. The other work showcased on his website is much more in an urban-centered reportage and social documentary vein. The other example, perhaps, I have in mind is the work of German photographer

Axel Hütte (a pupil of Bernd Becher) who produces bleak, understated landscapes (some of them in a mountaineous setting).

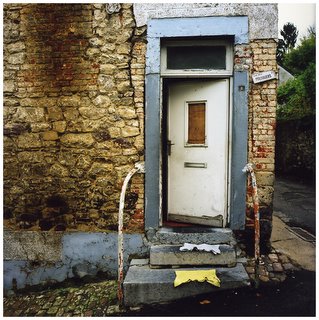

Perhaps a word on the image accompanying this blog entry. It is a picture taken by myself in the early nineties (Olympus OM-10, Zuiko 35/2.8, Ilford HP5). That must have been the only time I have put a B&W roll in my camera before I started to photograph in earnest. I remember that I was hugely disappointed in the pictures at the time, particularly because of the artificial, cardboard-like textures of the rocks. A lot was due, however, to the lacklustre printing in the lab I used back then. I rediscovered the negatives ten years later and now I’m sorry I didn’t take more pictures on that early-summer traverse through the Brenta Dolomites …

A new series of pictures has been added to our "Dubruk" website. Dubruk is a shared photographic scrapbook between Johan Doumont and myself.

A new series of pictures has been added to our "Dubruk" website. Dubruk is a shared photographic scrapbook between Johan Doumont and myself.